How Google’s Most Expensive AI Model Beat a 29-Year-Old Classic (With a Little Help)

- Google’s Gemini 2.5 Pro AI model has successfully completed Pokémon Blue, a 29-year-old GameBoy classic, marking a significant achievement in AI gaming capabilities.

- While the project was spearheaded by an independent software engineer, Joel Z, Google executives like CEO Sundar Pichai have celebrated the milestone, highlighting Gemini’s progress over competitors like Anthropic’s Claude.

- The victory required human intervention and specialized tools, raising questions about direct AI comparisons, but it showcases the potential of AI in tackling complex, unexpected tasks.

In a world where artificial intelligence continues to push boundaries, Google’s latest triumph has captured the attention of tech enthusiasts and gamers alike. Last night, Google CEO Sundar Pichai took to X to celebrate a remarkable feat: Gemini 2.5 Pro, one of Google’s most advanced AI models, has officially completed Pokémon Blue, a beloved GameBoy title first released in 1996. This achievement isn’t just a nostalgic win for fans of the long-running Pokémon franchise; it represents a fascinating milestone in the evolution of AI, demonstrating how far these models have come in handling intricate, unpredictable challenges.

The journey to this victory, however, wasn’t a solo endeavor by Gemini. The “Gemini Plays Pokémon” livestream, which documented the AI’s progress, was created by Joel Z, a 30-year-old software engineer who explicitly states he is unaffiliated with Google. Despite his independent status, Joel’s project has garnered significant attention and support from Google’s top brass. For instance, Logan Kilpatrick, the product lead for Google AI Studio, shared updates last month about Gemini’s progress, noting that it had earned its fifth badge in the game—ahead of competing models like Anthropic’s Claude, which has been tackling Pokémon Red (a sibling version of Blue) but has yet to finish. Pichai himself chimed in with a playful remark about developing “API, Artificial Pokémon Intelligence,” underscoring the excitement within Google about this unconventional application of their technology.

Why Pokémon, you might ask? The choice of a nearly three-decade-old video game as a testing ground for cutting-edge AI isn’t as random as it seems. Earlier this year, Anthropic, a rival AI company, showcased the progress of its Claude models in playing Pokémon Red, emphasizing how “extended thinking and agent training” enabled the AI to excel in unexpected tasks. This inspired Joel Z, who cited the “Claude Plays Pokémon” Twitch channel as a key influence for his own project. Pokémon games, with their mix of strategy, exploration, and problem-solving, offer a unique sandbox for testing an AI’s ability to adapt and reason through complex scenarios—skills that extend far beyond gaming into real-world applications.

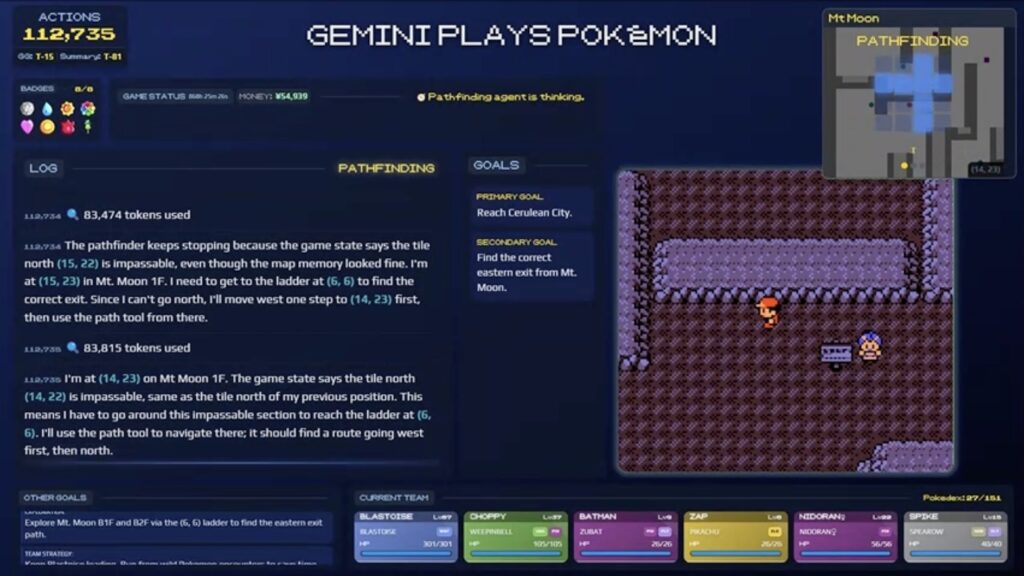

Yet, while Gemini’s completion of Pokémon Blue is undeniably impressive, it doesn’t necessarily mean it’s “better” at the game than Claude or other models. Joel Z himself cautions against viewing this as a definitive benchmark for large language models (LLMs) in gaming. On his Twitch page, he explains that direct comparisons are tricky since Gemini and Claude operate with different tools and access to information. Both AIs rely on “agent harnesses”—specialized frameworks that provide game screenshots overlaid with contextual data, enabling the models to make decisions, call on additional agents if needed, and execute actions like button presses. These harnesses, along with other developer interventions, were crucial to Gemini’s success, though Joel insists they don’t constitute cheating.

Delving deeper into these interventions, Joel clarifies that his role was to enhance Gemini’s decision-making and reasoning capabilities rather than spoon-feed it solutions. He avoided using walkthroughs or giving specific hints for challenges like navigating Mt. Moon, a notoriously tricky area in Pokémon Blue. The closest he came to direct guidance was informing Gemini that it needed to speak to a Rocket Grunt twice to obtain the Lift Key—a quirk in the game’s design that was later fixed in Pokémon Yellow. Even with this assistance, the achievement remains significant, as it highlights how AI can learn and adapt with minimal human input, paving the way for more autonomous problem-solving in future iterations.

The “Gemini Plays Pokémon” project is far from a finished product. Joel emphasizes that the framework is still actively evolving, with ongoing refinements to improve how the AI interacts with the game. This iterative process mirrors the broader development of AI technologies, where each milestone—however niche or playful—contributes to a deeper understanding of what these models can achieve. Google’s enthusiasm for the project, evidenced by Pichai’s and Kilpatrick’s public endorsements, suggests that even seemingly trivial applications like beating a retro video game can offer valuable insights into AI’s potential.

So, what does Gemini’s victory over Pokémon Blue mean for the future? On one level, it’s a delightful blend of nostalgia and innovation, reminding us of the cultural impact of games like Pokémon while showcasing AI’s growing prowess. On a deeper level, it raises intriguing questions about how we measure AI performance and the role of human collaboration in unlocking its full potential. While Gemini needed a little help to cross the finish line, its success hints at a future where AI could tackle far more complex challenges—perhaps not just in virtual worlds, but in real ones too. For now, though, let’s celebrate this quirky triumph: a 29-year-old game has been bested by a cutting-edge AI, proving that even in the realm of pocket monsters, technology reigns supreme.