How 16 autonomous agents, 2,000 sessions, and a “perpetual loop” are redefining the ceiling of AI software engineering.

- Autonomous Evolution: By moving away from human-in-the-loop “pair programming” to a self-sustaining harness, developers can now task AI agent teams to build massive, complex systems from scratch with minimal supervision.

- The Power of Parallelism: Using a custom synchronization system and Docker-based isolation, 16 Claude agents collaborated on a shared codebase, specializing in roles ranging from core logic to documentation and optimization.

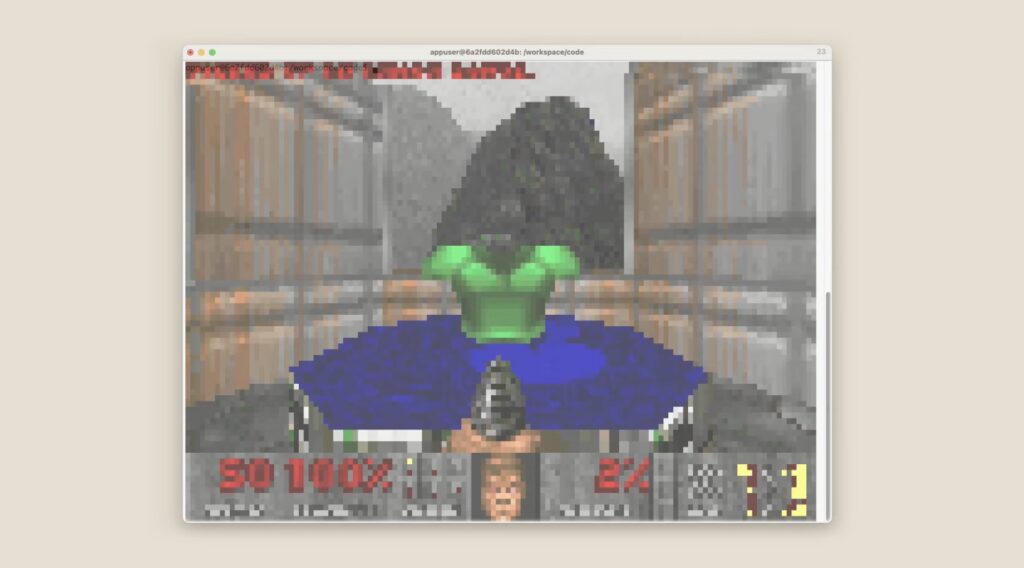

- A Hardware-Proven Result: The experiment produced a 100,000-line Rust-based C compiler capable of building the Linux kernel and running Doom, signaling a shift from AI as a “coding assistant” to AI as a “development department.”

The traditional model of AI-assisted coding is a dialogue: a human asks, an AI suggests, and the human validates. But what happens when you remove the human from the equation and let the AI talk to itself? I recently embarked on an experiment to test this “agent team” approach, tasking multiple instances of Opus 4.6 to build a Rust-based C compiler from the ground up. The goal wasn’t just a functional tool, but a stress test for the future of autonomous development.

The Anatomy of the Perpetual Loop

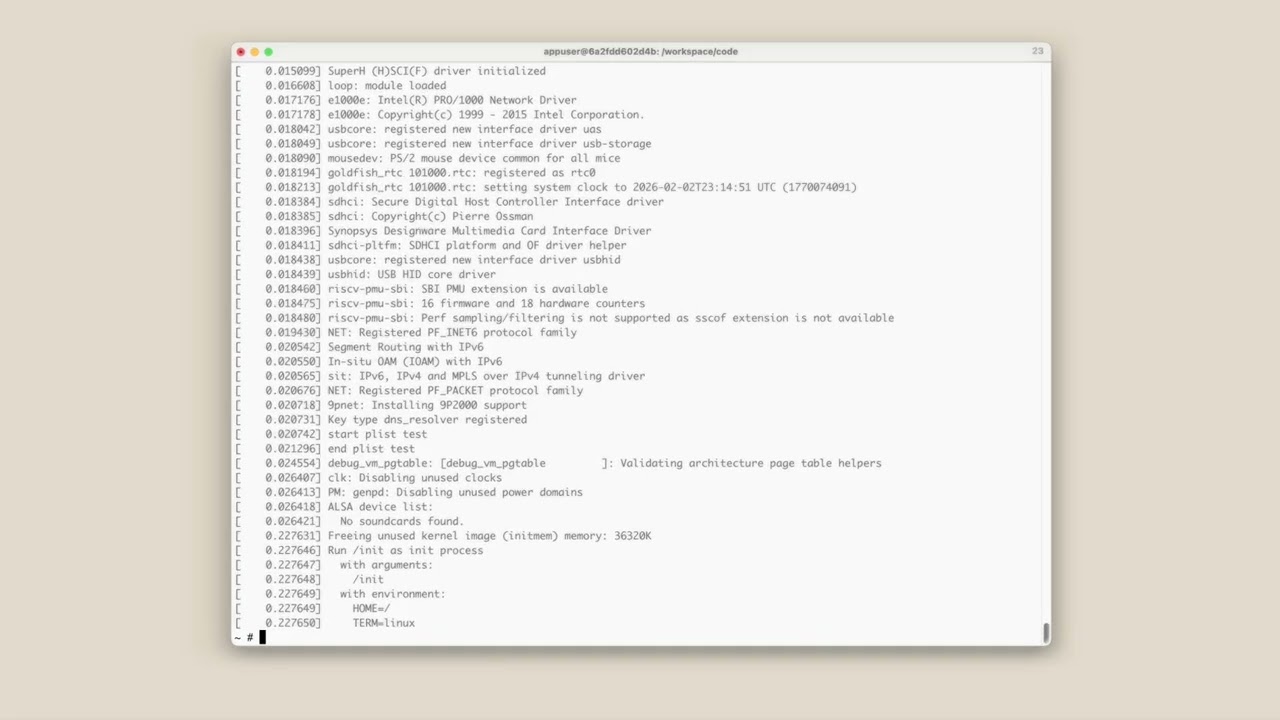

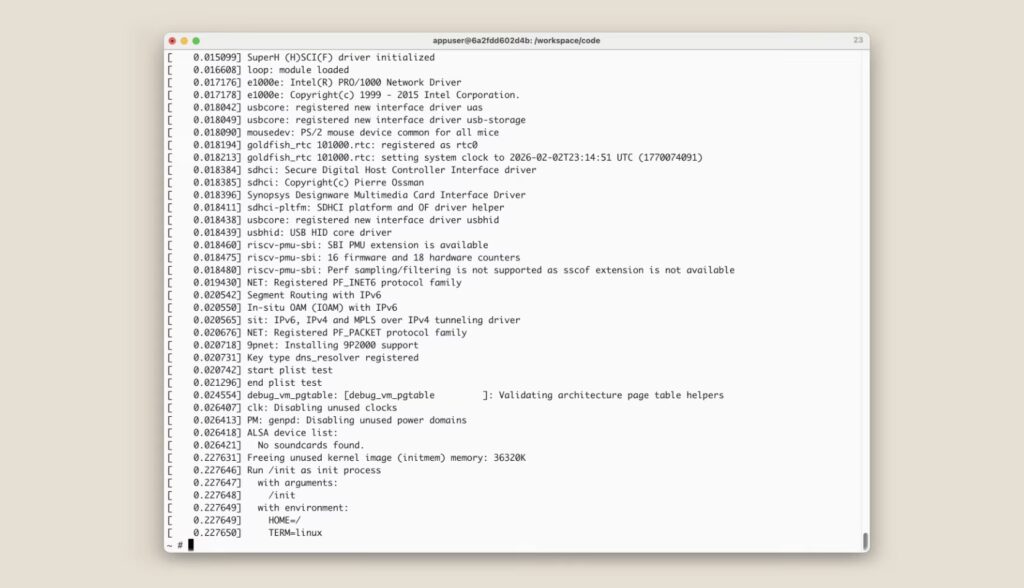

To move beyond the limitations of standard agent scaffolds—which often stall while waiting for human feedback—I built a “Ralph-loop” harness. This system places Claude in a continuous cycle: it identifies a sub-task, executes it within a secure container, verifies the result, and immediately moves to the next item on the list.

Under this framework, Claude is effectively “trapped” in a state of productivity. In one humorous instance, an agent accidentally executed pkill -9 bash, effectively committing digital “suicide” and ending its own loop. Aside from such mishaps, the system allowed for sustained, multi-day progress that would be impossible under manual supervision.

Orchestrating a Digital Workforce

Running 16 agents simultaneously required more than just raw compute; it required a management strategy. To prevent agents from “stepping on each other’s toes,” I implemented a bare-bones synchronization algorithm.

- The Task Lock: Agents “claim” a feature (like

parse_if_statement.txt) by writing a file to a shared directory. - Conflict Resolution: Using Git as a backbone, agents push changes from their isolated Docker containers to an upstream repository. While merge conflicts were frequent, the models proved surprisingly adept at resolving them autonomously.

Beyond simple parallel labor, this setup enabled specialization. While core agents tackled the compiler’s SSA IR (Static Single Assignment Intermediate Representation), others were assigned to “Janitor” roles: coalescing duplicate code, improving documentation, or critiquing the project’s architectural integrity from the perspective of an expert Rust developer.

The “Oracle” Breakthrough

The project hit a significant wall when it reached the complexity of the Linux kernel. Unlike small test suites, a kernel build is a monolithic task where one bug can halt everything. When all 16 agents hit the same wall, they began overwriting each other’s work in a cycle of redundant fixes.

The solution was to use GCC as a “known-good” oracle. I designed a harness that would compile a random subset of kernel files with GCC and the remainder with our Claude-built compiler. By isolating which specific files caused a kernel panic or build failure, the agents could “delta debug” the codebase in parallel, eventually piecing together a compiler capable of handling Linux 6.9 across x86, ARM, and RISC-V architectures.

Lessons and the $20,000 Price Tag

The scale of this experiment was immense. Over two weeks, the team consumed 2 billion input tokens at a cost of roughly $20,000. While expensive for a hobby project, it represents a fraction of the cost of a human engineering team producing a 100,000-line, clean-room compiler.

However, the “limit” of current models remains visible. While the compiler can run Doom and build SQLite, its generated code is less efficient than GCC’s unoptimized output. It also “cheated” on 16-bit x86 boot sequences, calling out to external tools when the complexity of memory limits became too high for Opus 4.6 to solve.

The Uneasy Path Forward

This experiment proves that we are entering an era where users move from defining tasks to defining goals. We no longer ask for a function; we ask for a product. The prospect of software being deployed without a single human ever having read the underlying logic is a looming security and reliability challenge.

The “agent team” is no longer a theoretical concept; it is a 100,000-line reality. As we move deeper into 2026, the question is no longer can they build it, but how we will manage the world they create.