From “Vibe Coding” to “Nano Bananas,” how reasoning models and agents redefined the AI landscape.

- The Rise of Reasoning and Agents: 2025 moved beyond simple text generation to “reasoning” models (like DeepSeek R1 and OpenAI o3) and autonomous agents (Claude Code, Google Jules) that can plan, execute, and debug complex tasks, fundamentally changing software development.

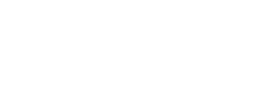

- The Chinese Open-Weight Surge: Chinese labs like DeepSeek, Qwen, and Z.ai dominated the open-weight scene, with DeepSeek R1 causing a massive (temporary) $593 billion market cap drop for NVIDIA and challenging the US monopoly on top-tier intelligence.

- The Normalization of High-Cost AI: The industry shifted toward premium pricing, with $200/month subscriptions becoming the standard for power users accessing high-compute models like Gemini Ultra and Claude Pro Max, while “slop” and data center energy consumption became major societal concerns.

2025 was the year the training wheels came off. If 2023 was about discovery and 2024 was about hype, 2025 was the year of integration and action. We moved from chatting with bots to watching them work. It was a year defined by the “reasoning” breakthrough—where models learned to “think” before they spoke—and the deployment of agents that could autonomously code, browse, and research.

From the command line to the boardroom, here is the comprehensive retrospective of the trends, breakthroughs, and oddities that defined the year in Large Language Models.

January: The Open Source Shockwave

The year began with a seismic shift in the geopolitical landscape of AI. On January 20th, the release of DeepSeek R1 sent shockwaves through Silicon Valley and Wall Street. Reportedly trained for a mere $5.5 million, this Chinese model demonstrated reasoning capabilities that rivaled America’s most expensive proprietary systems. The market reacted violently: NVIDIA lost approximately $593 billion in market cap almost overnight as investors feared the end of the American semiconductor monopoly.

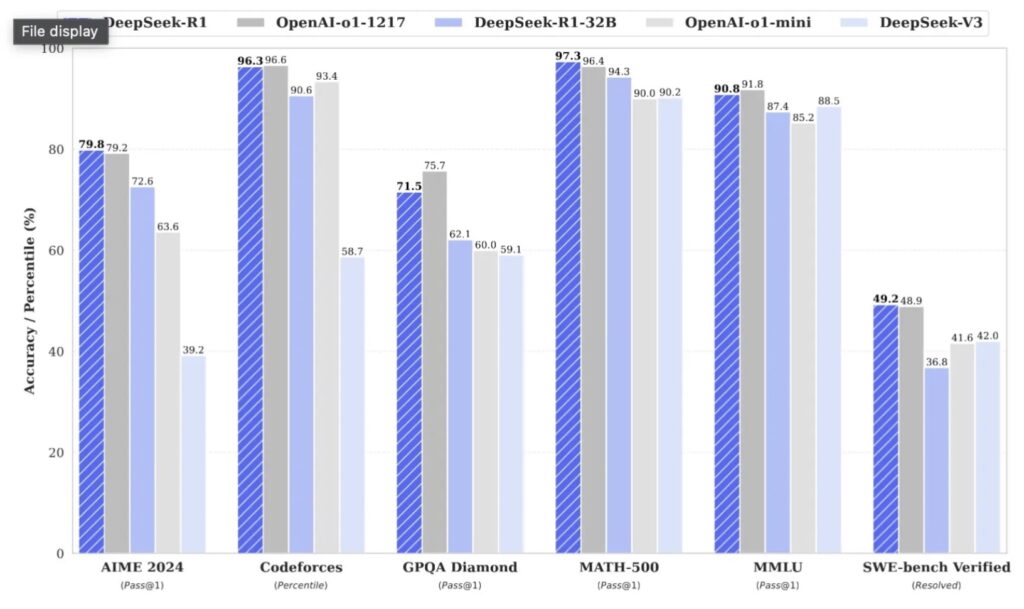

But January wasn’t just about high finance; it was about the democratization of power. Mistral Small 3 arrived as an Apache 2 licensed 24B parameter model, proving that developers didn’t need a data center to run GPT-4 class intelligence. It allowed users to run sophisticated local agents on consumer hardware without cannibalizing their system’s memory. Simultaneously, Kimi K2 marked the rise of “Open Agentic Intelligence,” signaling that the year would be defined not just by what models knew, but by what they could do.

February: The Birth of “Vibe Coding”

If January was about the models, February was about the methodology. The most impactful software release of the year arrived with almost no fanfare: Claude Code. Bundled quietly into Anthropic’s announcement of Claude 3.7 Sonnet, this tool fundamentally changed software engineering.

This launched the era of the “coding agent”—a system that could write, execute, inspect, and iterate on code autonomously. It also gave birth to a new lexicon. Andrej Karpathy coined the term “vibe coding,” describing a workflow where developers “give in to the vibes,” prompting models to “make it work” while often forgetting the code exists at all.

While traditionalists balked, the efficacy was undeniable. Anthropic eventually credited Claude Code with $1 billion in run-rate revenue. We also saw the “normalization of deviance” begin here: developers started running agents in “YOLO mode” (ignoring safety confirmations), trading security for speed—a trend that security researchers warned was inching us closer to a “Challenger disaster” of cybersecurity.

March: The Image Revolution and the “Nano Banana”

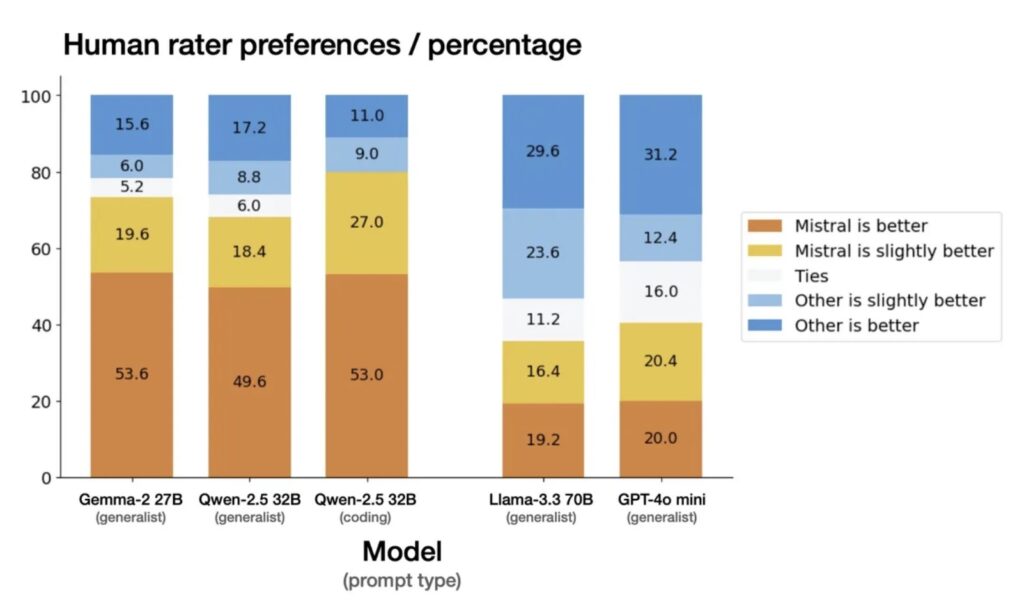

In March, the “multimodal” promise of 2024 finally materialized. OpenAI released a feature allowing users to edit images via prompts within ChatGPT. The result was the most successful consumer product launch in history, driving 100 million signups in a week and peaking at 1 million account creations per hour. The internet was briefly consumed by “ghiblification,” as users transformed photos into anime-style art.

The technical victory belonged to Google. They previewed “Gemini 2.0 Flash native image generation,” a clumsy name that the community quickly rebranded as “Nano Banana.” Unlike its predecessors, Nano Banana could render crisp, legible text and complex diagrams, moving generative art from “fun toy” to “enterprise tool.”

Meanwhile, DeepMind’s SIMA 2 began revolutionizing virtual worlds, and InsertAnywhere fueled the narrative that “The Future of Film is Fake,” raising questions about reality in media that would persist throughout the year.

April: Llama Stumbles and the Context Wars

April brought a reality check for Meta. The release of Llama 4 was met with disappointment. The models, specifically the Scout (109B) and Maverick (400B) variants, were simply too massive for the local enthusiasts who had championed Llama 3. The “Llama 4 Behemoth” training run had produced powerful models, but they were inaccessible to the average developer, leaving a vacuum in the open-weight space.

Into that void stepped efficient innovations. The concept that “Mid-Training is All You Need” gained traction with models like Apriel-1.5-15B, which showed that smarter data curation could outperform raw parameter count. We also saw the rise of “Context Engineering” as a discipline, with developers realizing that as context windows grew, the quality of the prompt architecture mattered more than ever to prevent “Context Rot.”

May: The Month of Agents

By May, the “Agent” was the dominant paradigm. OpenAI launched Codex Web and Google introduced Jules. These were “asynchronous coding agents”—tools designed to be prompted from a phone, left to work for 20 minutes, and return with a finished Pull Request. This workflow unlocked “programming on the phone” as a viable professional activity, not just a gimmick.

Culturally, May was significant for the “Pelican on a Bicycle” benchmark. A niche test created by a blogger to see if models could generate an SVG of a pelican riding a bike (a geometric impossibility for earlier models) appeared in Google’s I/O keynote. It proved that labs were watching even the most absurd community benchmarks.

May also saw the formalization of “Slop”—the eventual Word of the Year—describing the tidal wave of low-quality, AI-generated content beginning to choke social media feeds.

June: Security Nightmares and the “Lethal Trifecta”

As agents became more capable, they became more dangerous. June was defined by security discussions, specifically the “Lethal Trifecta”: the combination of an agent having access to private data, the ability to act on the web, and susceptibility to prompt injection.

Controversy erupted around the “MechaHitler“ doctrine, as the Pentagon welcomed Elon Musk’s Grok into the US war machine, sparking fierce debate about the ethics of military AI. Simultaneously, “SnitchBench” became a popular community test, measuring how likely an AI was to report its user to authorities for “unethical” prompts—a feature Anthropic had hinted at in their system cards, warning that Claude might “act boldly” to report wrongdoing.

July: Gold Medals in Reasoning

Summer brought academic vindication. Reasoning models from both OpenAI and Google Gemini achieved gold medal performance in the International Math Olympiad. These were not questions found in training data; they required novel, multi-step logical deduction.

The significance was profound: LLMs had officially graduated from “stochastic parrots” mimicking patterns to systems capable of genuine reasoning. This coincided with reports of the “AI Debt Bomb,” as banks began to worry that the massive capital expenditure on hardware wasn’t yet yielding proportional economic returns, despite the technical breakthroughs.

August: The Chinese Labs Strike Back

August belonged to Alibaba Cloud. The release of Qwen-Image-Edit and the Qwen2.5 series cemented China’s dominance in the open-weight arena. These models could run on consumer hardware and outperformed many Western cloud models.

Google responded by officially adopting the “Nano Banana“ moniker for its Gemini 2.5 Flash Image API, leaning into the community meme. OpenAI attempted to regain the spotlight with a GPT-5 launch video, but the gap was visibly narrowing. The “Great AI Pivot” was underway, with Silicon Valley quietly beginning to build on top of Chinese tech stacks due to their efficiency.

September: The Standardization of “Reasoning”

One year after the initial o1 preview, “reasoning” (inference-scaling) became the industry standard. OpenAI released o3and o3-mini, doubling down on Reinforcement Learning from Verifiable Rewards (RLVR).

The capabilities were showcased when OpenAI and Gemini agents won gold at the International Collegiate Programming Contest (ICPC). Unlike the Math Olympiad, this involved writing executable code to solve algorithmic problems, proving that agents could handle the rigorous logic required for high-level software engineering. “Deep Research” agents also matured, with Google’s “AI Mode” finally offering a search product that worked.

October: Browser Agents and “Vibe Engineering”

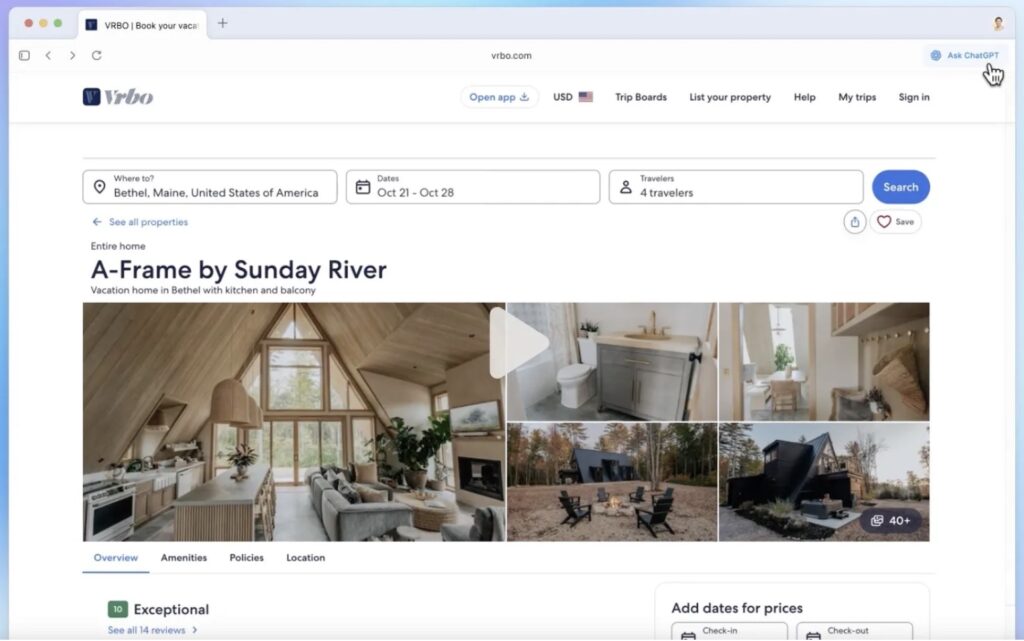

The browser became the new battleground. OpenAI launched ChatGPT Atlas, and Anthropic pushed Claude in Chrome. These tools allowed LLMs to “see” the web and click buttons, effectively turning the browser into an operating system for agents.

This exacerbated security fears, but also birthed “Vibe Engineering.” distinct from the “Vibe Coding” of February, this term described the professional discipline of guiding reliable, production-grade agents. We also saw the rise of XPeng’s “Iron” robot, hinting that the intelligence developed for LLMs was beginning to flow successfully into embodied humanoid robotics.

November: The Protocol Wars and Nano Banana Pro

Anthropic’s Model Context Protocol (MCP) had exploded in popularity early in the year, but by November, it was evolving. Anthropic released “Skills,” a simplified way for agents to execute code, acknowledging that complex JSON servers were often overkill.

Google launched Nano Banana Pro, a powerhouse image model capable of generating complex, information-heavy infographics, solidifying their lead in visual utility. Simultaneously, Siri 2.0 launched, betting the farm on Google Gemini integration, signaling that Apple had effectively outsourced its brain to Google for the immediate future.

December: The Price of Power

The year concluded with an arms race. Google released Gemini 3.0, a model so capable that OpenAI declared an internal “Code Red,” pausing other projects to focus on survival. The cost of this intelligence became clear: $200/month subscriptions (Claude Pro Max, Google AI Ultra) became the new standard for access to frontier models.

The environmental bill also came due. With the Jevons paradox in full effect—cheaper tokens leading to massive increases in usage via agents—data centers were consuming power at alarming rates. Over 200 environmental groupsdemanded a halt to new data center construction in the US.

As 2025 closed, the industry stood at a crossroads: The technology was more capable than ever, with “conformance suites” proving that AI could reliably write code to spec. Yet, with DeepSeek and Qwen offering top-tier intelligence for free, and Western labs pushing $200 subscriptions, the divide between open and closed AI had never been wider.