Navigating the Promises and Perils of AI in Young Lives

- Generative AI is increasingly integrated into children’s lives through tools like ChatGPT and Dall-E, with nearly a quarter of kids aged 8-12 already using these technologies for creativity, learning, and play.

- Research reveals a mix of optimism and concern among parents, carers, and teachers, highlighting benefits like support for children with additional learning needs, alongside risks such as exposure to inappropriate content and impacts on critical thinking.

- The Alan Turing Institute’s child-centered study, guided by the RITEC framework, underscores the urgent need for safe, responsible AI development with children’s rights and wellbeing at the forefront, offering actionable recommendations for policymakers and industry.

Generative AI is no longer a futuristic concept; it’s a present reality shaping the digital landscape where children play, learn, and grow. From crafting whimsical images on Dall-E to seeking homework help via ChatGPT, nearly a quarter of children aged 8-12 in the UK are engaging with these tools, with 22% using them monthly or more. This rapid adoption, as uncovered by the Alan Turing Institute’s Children and AI and AI for Public Services teams, signals a transformative shift in how young minds interact with technology. Yet, while the potential for creativity and learning is immense, the risks and unknowns loom large, especially for a group so often sidelined in tech governance discussions. This article delves into the multifaceted impacts of generative AI on children, drawing from comprehensive research funded by the LEGO Group and guided by UNICEF’s Responsible Innovation in Technology for Children (RITEC) framework, to explore how we can harness its benefits while safeguarding our youngest users.

The research, combining surveys of 780 children aged 8-12, their parents or carers, and 1,001 teachers, with qualitative school-based workshops, paints a vivid picture of generative AI’s role in children’s lives. Tools like ChatGPT (used by 58% of child users), Gemini (33%), and Snapchat’s My AI (27%) are not just novelties but active components of learning and play. Children are using these technologies to spark creativity, with 43% creating fun pictures or seeking information, and 40% engaging for entertainment. Usage patterns vary intriguingly by age and need—8-year-olds lean toward entertainment, while 12-year-olds often seek homework support. Notably, children with additional learning needs show higher engagement, with 78% using ChatGPT compared to 53% of their peers, often for communication and connection, such as expressing thoughts they struggle to articulate (53% vs. 20% of peers without such needs). This suggests generative AI could be a powerful ally in inclusive education if developed responsibly.

However, the digital playground isn’t without its shadows. A stark disparity emerges in access and attitudes between private and state schools, with 52% of private school children using generative AI compared to just 18% in state schools, and 72% of private school users engaging weekly versus 42% in state settings. Teachers in private schools also report greater awareness of student usage (57%) than their state counterparts (37%). This inequity raises questions about fair access to emerging technologies and the need for broader AI literacy programs. Beyond access, concerns about content safety are paramount. Parents and carers, despite 76% feeling positive about their children’s AI use, overwhelmingly worry about exposure to inappropriate (82%) or inaccurate (77%) information. Workshops further revealed that even simple prompts can generate harmful outputs, underscoring the urgency of robust safeguards—a risk not shown to children in the study due to strict protocols but a real concern for unsupervised use.

The impact on critical thinking is another shared worry among adults, with 76% of parents and 72% of teachers fearing children may overly trust AI outputs, stunting their analytical skills. Teachers, while optimistic about their own use of generative AI (85% report increased productivity and 88% feel confident in it), are more cautious about student impacts. Nearly half (49%) believe it reduces class engagement, and 48% note less diversity in student ideas. A troubling 57% of teachers aware of student AI use report children submitting AI-generated work as their own, a practice more noted in state schools (60%) than private (47%). Yet, there’s a silver lining—64% of teachers see AI as a valuable tool for students with additional learning needs, aligning with children’s own workshop feedback that AI could support diverse learning styles.

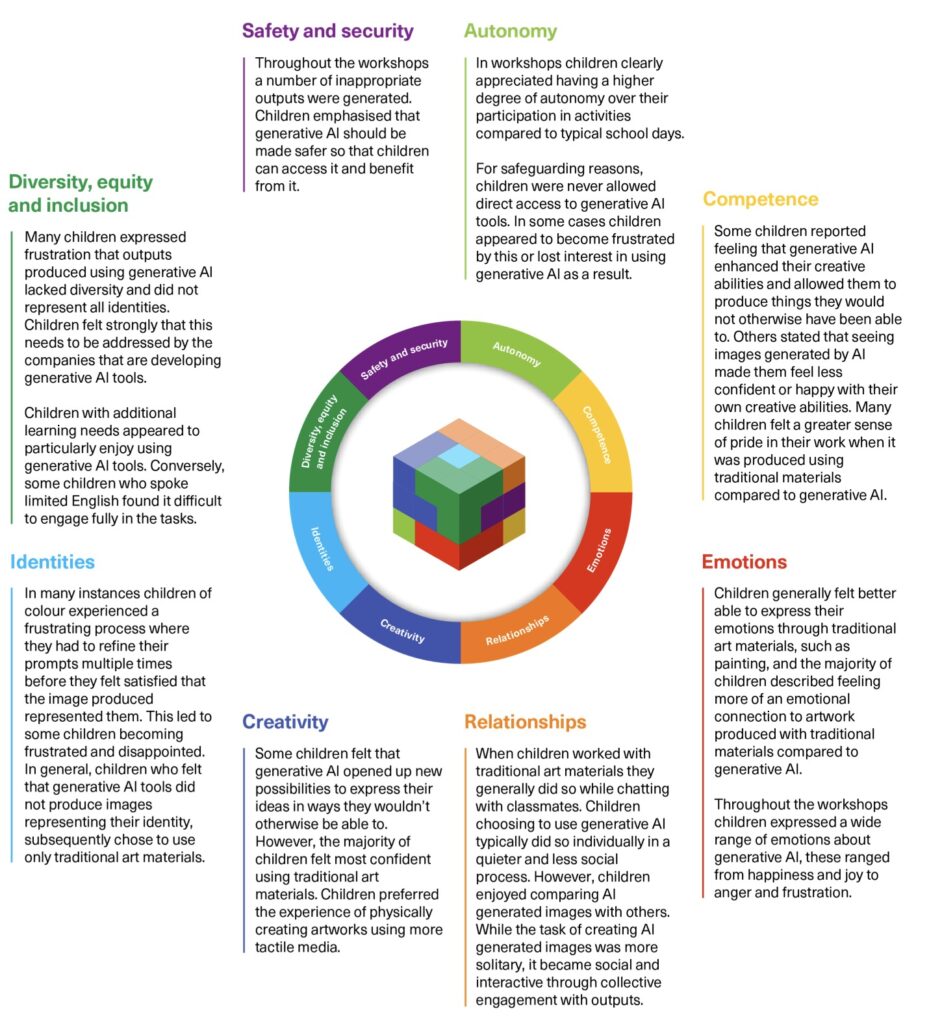

Diving deeper into children’s perspectives, the research’s child-centered approach reveals nuanced insights often missed in adult-dominated discussions. Workshops showed children capable of complex conversations about AI, weighing its potential against its pitfalls. Some grew less enthusiastic after using tools that failed to reflect their identities—particularly children of color who felt frustrated by unrepresentative outputs. This highlights a critical gap in AI design: the need for inclusivity to ensure tools resonate with diverse users. Meanwhile, surveys noted that more experience with AI often correlates with positive attitudes among children and teachers, though hands-on workshop experiences sometimes shifted opinions negatively if outputs disappointed. These findings emphasize that children’s voices must be central to AI development, not an afterthought, as they navigate when and how to use these tools with surprising discernment when informed.

Parents, carers, and teachers, while sharing concerns, also display varied optimism. Teachers trust AI in their own work (61% report trust in systems used), with 82% noting a positive impact on teaching. Yet, their reservations about student use contrast with parents’ lower concern about cheating (only 41% worried) compared to content risks. This discrepancy suggests a need for aligned education on AI’s role in learning environments. The research’s blend of quantitative breadth and qualitative depth offers a holistic view, showing that while generative AI holds promise—especially for supporting unique learning needs—it demands urgent attention to risks like harmful content and inequitable access.

Turning to solutions, the study’s recommendations, rooted in stakeholder perspectives, call for a balanced approach. Generative AI can benefit children if developed safely with their input, but current gaps in involvement, low AI literacy, harmful content risks, and environmental impacts must be addressed. Key actions include prioritizing children’s rights in AI design, enhancing digital literacy across all educational settings, and enforcing strict content filters to protect young users. Industry and policymakers are urged to involve children meaningfully in development processes, ensuring tools reflect diverse identities and needs. Additionally, addressing the digital divide between private and state schools is critical to prevent widening inequalities in tech access and skills.

Generative AI is reshaping childhood in ways both exciting and daunting. It offers a canvas for creativity and a bridge for learning challenges, yet poses real risks to safety, equity, and critical thinking. The Alan Turing Institute’s research, through the RITEC framework, not only amplifies children’s often-ignored voices but also charts a path forward. By embedding responsibility and inclusivity into AI’s evolution, we can transform this digital playground into a space where children thrive—protected, empowered, and inspired. The question remains: will we prioritize their wellbeing in this tech-driven future, or let them navigate the perils alone?