A critical look at why high reconstruction scores might be masking a fundamental failure in AI interpretability.

- The Reconstruction Paradox: SAEs can explain a high percentage of model variance (71%) while failing to recover the vast majority of actual ground-truth features (only 9%).

- The Random Baseline Challenge: Simple baselines using random feature directions perform nearly as well as fully-trained SAEs in interpretability, probing, and causal editing.

- A Call for New Objectives: The current reliance on “reconstruction loss” encourages sparse data compression rather than the discovery of the model’s true internal mechanisms.

In the quest to peer inside the “black box” of Large Language Models (LLMs), Sparse Autoencoders (SAEs) have become the star of the show. The promise is seductive: take the messy, high-dimensional activations of a frontier model and decompose them into neat, human-understandable “features.” We’ve seen the headlines—researchers finding “Golden Gate Bridge” neurons or specific clusters for legal jargon. However, a growing body of evidence suggests we might be celebrating a clever facade rather than a true map of machine intelligence.

The Synthetic Reality Check

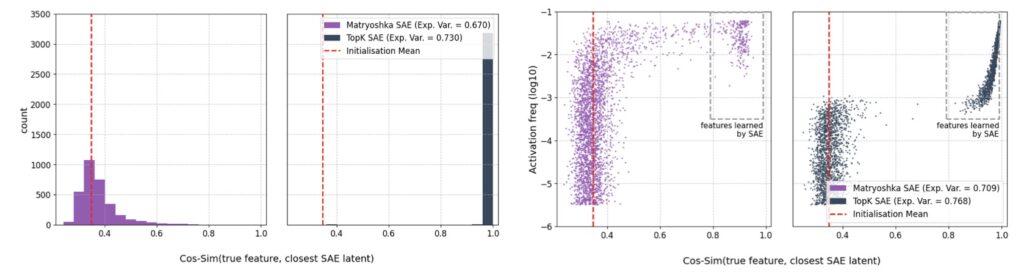

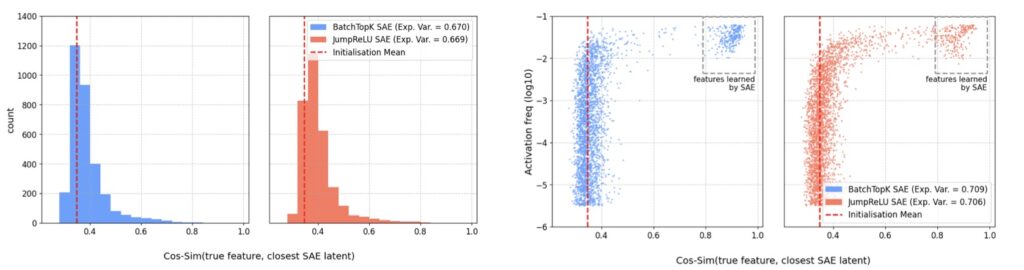

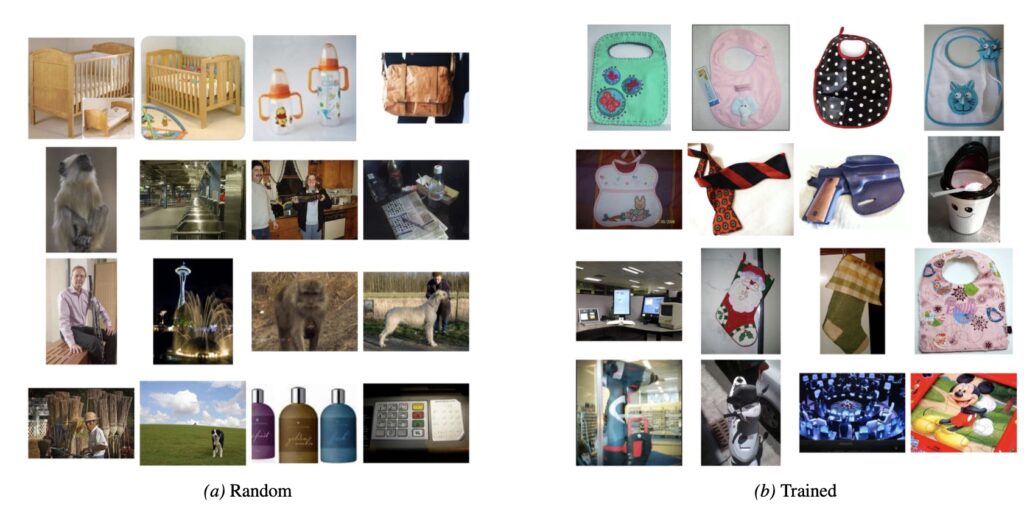

To test whether SAEs actually do what they say on the tin, researchers recently moved the goalposts to a controlled environment. By using synthetic data where the “ground-truth” features were known beforehand, they could measure exactly how many features the SAE correctly identified.

The results were startling. While the SAEs were excellent at reconstructing the data—achieving an “explained variance” of 71%—they only managed to recover a meager 9% of the actual features. This reveals a dangerous disconnect: a model can be nearly perfect at mimicking the original signal without having any real grasp of the underlying concepts that created it. In the world of interpretability, high performance on paper does not equate to truth.

Can Randomness Rival “Learning”?

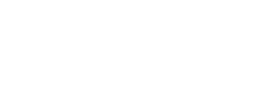

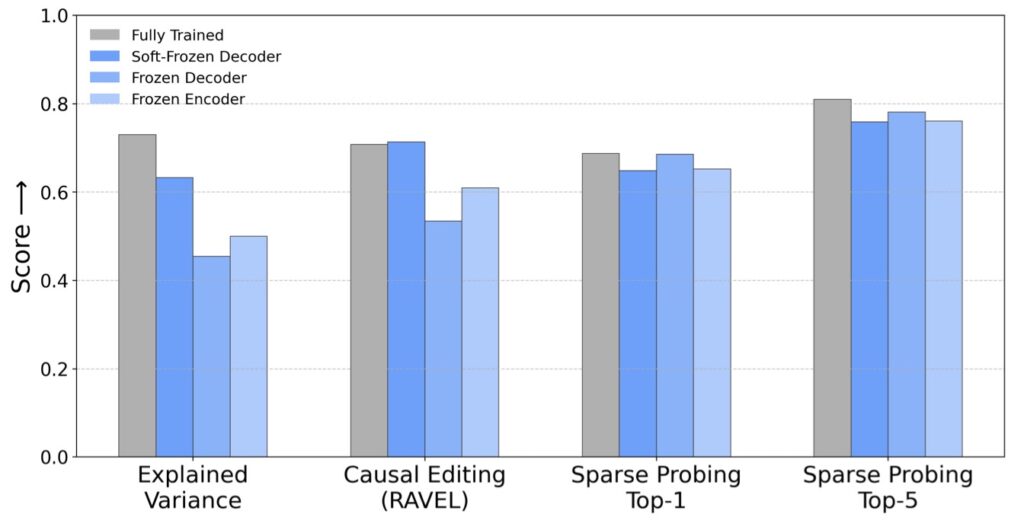

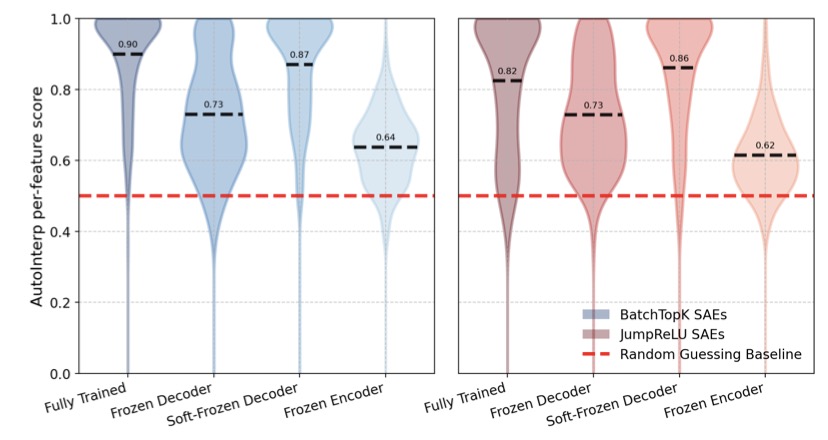

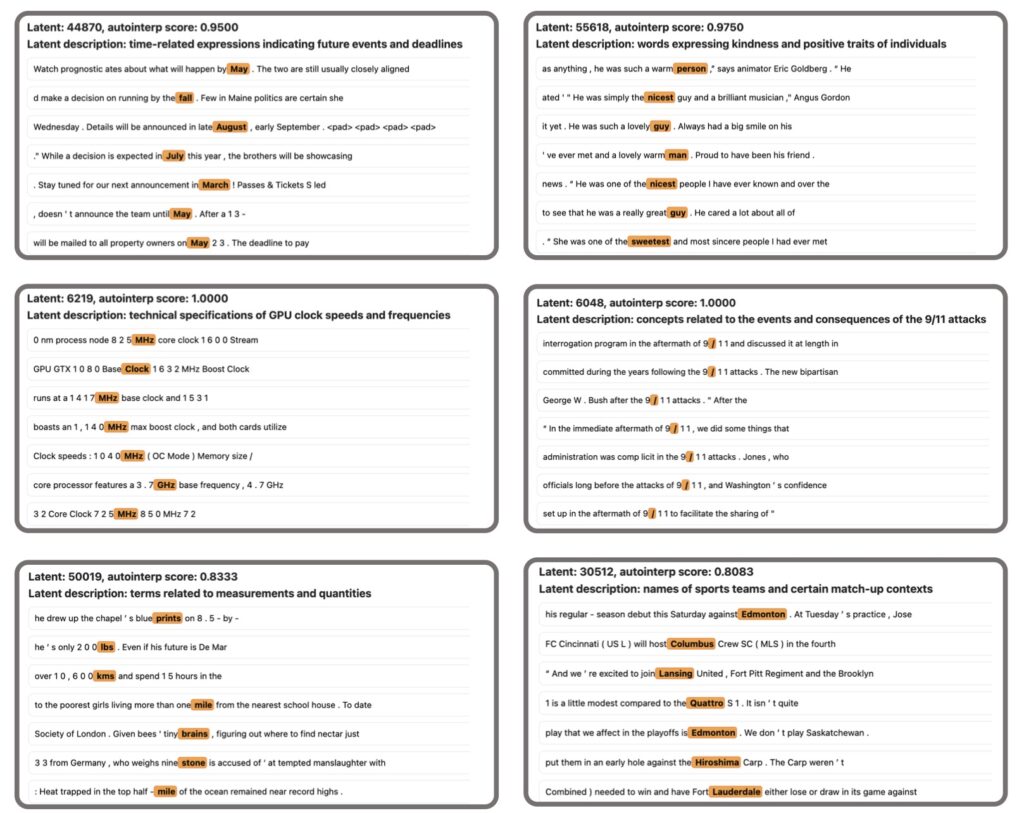

Perhaps the most humbling discovery comes from the introduction of “sanity check” baselines. Researchers compared fully-trained, computationally expensive SAEs against models where feature directions or activation patterns were constrained to random values.

If SAEs were truly capturing the “soul” of the model, they should theoretically blow these random baselines out of the water. Instead, the gap was razor-thin:

- Interpretability: 0.90 (Fully-trained) vs. 0.87 (Random)

- Sparse Probing: 0.72 (Fully-trained) vs. 0.69 (Random)

- Causal Editing: 0.72 (Fully-trained) vs. 0.73 (Random)

When a random baseline can match or even slightly outperform a trained model in causal editing, it suggests that the “learning” we thought was happening might actually be a byproduct of simple data sparsity rather than deep structural insight.

Why the Reconstruction Objective Fails

The root of the problem likely lies in the mathematical goal we set for these models. Currently, SAEs are trained to minimize reconstruction loss—essentially, they are told to “make the output look like the input” using as few features as possible.

The issue is that there are infinite ways to compress and decompress data. An SAE can find a mathematically efficient way to pack information that has nothing to do with the “true” features the LLM is actually using to think. We are rewarding the AI for being a good accountant of data, not a good translator of thought.

Toward More Rigorous Science

This isn’t a death knell for Sparse Autoencoders, but it is a necessary “sanity check” for the field of AI safety and interpretability. If we rely on these tools to ensure models are safe, honest, or unbiased, we must be certain they are showing us the real mechanisms under the hood, not just a random, sparse approximation.

Moving forward, the challenge for the AI community is to develop new training objectives—goals that move beyond simple reconstruction and toward feature alignment. Only then can we move from merely seeing “ghosts” in the machine to truly understanding the mind of the AI.